Artificial intelligence is no longer emerging, it’s now a primary driver of productivity, innovation, and disruption.

Artificial intelligence can no longer be considered an emerging technology; it is now the defining force reshaping work and modern economies. What began with the automation of repetitive tasks now reaches deep into the core of business, government, and society. Occupations once seen as immune, including those in the human, professional and creative sectors are being redefined in real time by AI and the exponential rise of large language models (LLMs).

LLMs are not only changing how we interact with information, but they are also becoming the cognitive infrastructure for agentic AI systems that can reason, plan, and take action autonomously. According to METR (2025), the efficiency of these models is doubling roughly every seven months. Tasks that once took an hour for a skilled developer are now executed in minutes. The implications are as vast as they are urgent: AI has the potential to drive unprecedented economic value while fundamentally redrawing the boundaries of human work.

As business leaders and policy makers grapple with these shifts, three questions come into focus. First, how will this new wave of automation reshape the labour market? Second, what kind of economy is emerging as AI drives productivity gains? And third, who will control the value AI creates, and on what terms?

In the sections that follow, this article explores the early signs of disruption in employment data, the growing divergence between productivity and job creation, and the troubling consolidation of technological power in the hands of a few. It calls for a coordinated national strategy, one that aligns business investment, workforce development, and forward-looking regulation to ensure AI delivers economic growth that is both inclusive and sustainable.

Early signs suggest automation is reshaping employment faster than government and industry had anticipated with young people and women particularly at risk.

In the UK, early indicators are stark: graduate and entry-level vacancies have dropped sharply across many sectors, and youth unemployment is climbing. The number of young people not in education, employment or training is at its highest in a decade. These are not passing symptoms of post-pandemic realignment, but early warning signs of a profound shift in the labour market.

Recent studies suggest that the share of job tasks exposed to AI-based automation has reached a tipping point. According to the International Labour Organisation, one in four jobs worldwide is now at high risk of disruption. Clerical and administrative roles, long a point of entry into the workforce, are among the most at risk. These jobs are disproportionately held by women, meaning the burden of disruption is not equally shared. Women face nearly three times the exposure rate of men when it comes to AI-related job risk. As automation accelerates, many women may find themselves more vulnerable to displacement with fewer clear pathways into emerging roles. In short, the AI revolution is not just rapid and far-reaching, it also threatens to deepen existing gender inequalities.

Proponents argue that every industrial revolution destroys and creates jobs in equal measure. But AI may be different. It is moving faster, affecting both manual and white-collar tasks simultaneously, and concentrating value creation in fewer hands. The analogy to the spinning jenny or steam engine is comforting but flawed. Earlier technological shifts occurred over decades. AI is transforming industries in quarters.

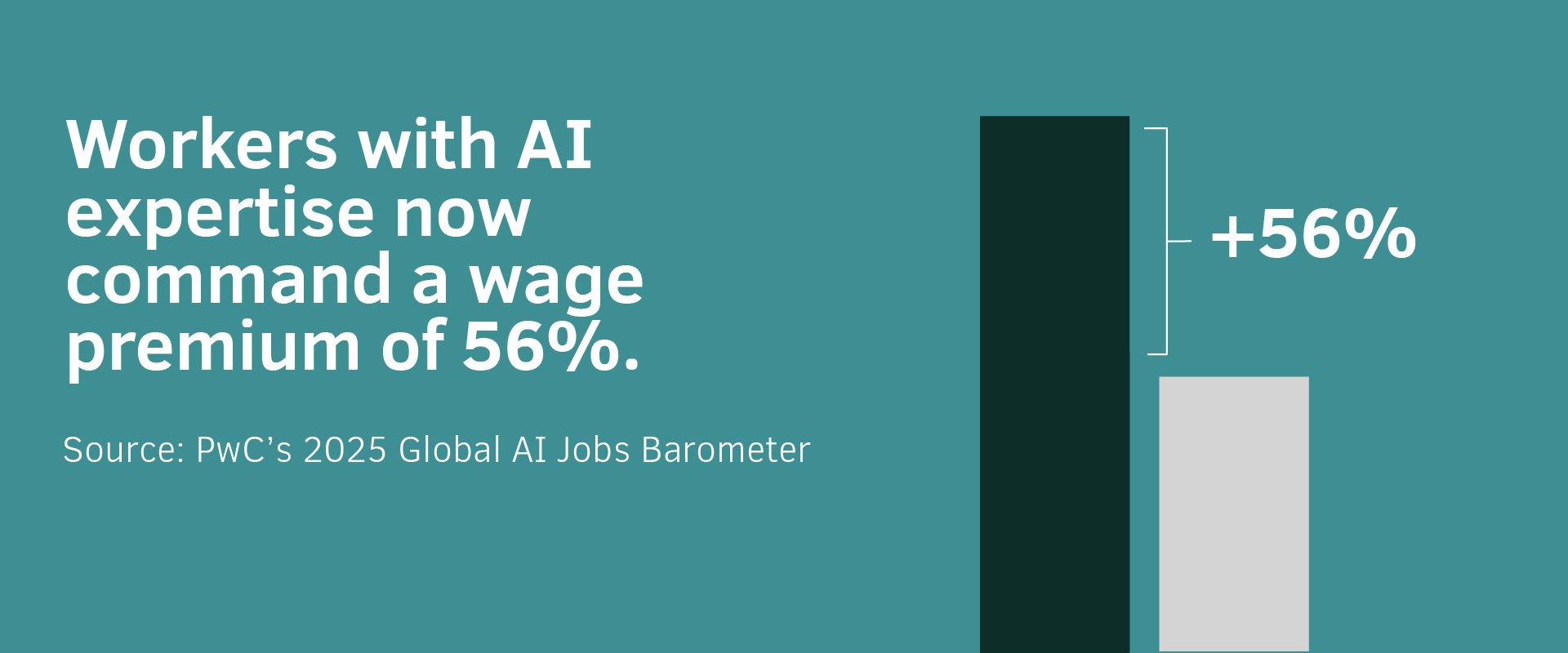

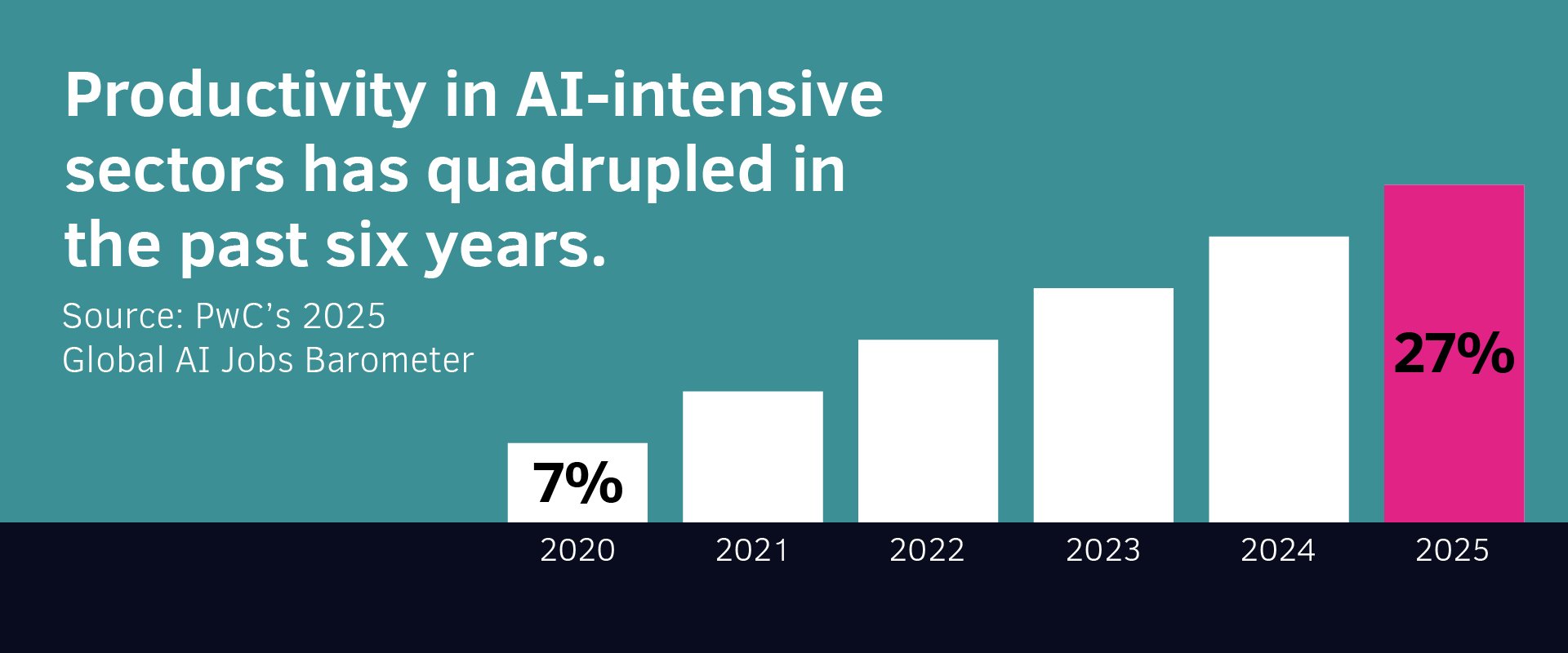

Paradoxically, this disruption comes amid booming productivity. According to PwC’s 2025 Global AI Jobs Barometer, productivity in AI-intensive sectors has quadrupled in the past six years, leaping from 7% to 27%. Wages in these sectors have outpaced others by a factor of two. Workers with AI expertise now command a wage premium of 56%. While this suggests a high-growth frontier for those with the right skills, it also reveals a widening fault line. While AI is driving record productivity gains and reshaping entire industries, those benefits are not automatically translating into broader job creation. In many cases, the returns are being captured through reinvestment in automation or distributed to shareholders bypassing the wider workforce. This decoupling of economic growth from employment risks hollowing out the middle of the labour market. GDP may rise, but the overall share of people participating in meaningful, well-paid work could decline.

This paradox is especially clear in sectors like healthcare, where AI has the potential to dramatically improve diagnostic accuracy, accelerate medical research, and extend life expectancy through earlier interventions and more precise treatment. However, even as outcomes improve, the system itself may come under increased pressure. As AI displaces workers in other parts of the economy, more people may find themselves reliant on publicly funded health services, intensifying demand on an already stretched system. In this way, AI may improve health outcomes while simultaneously increasing societal dependency on the very services it is designed to optimise and support.

The result is a two-speed economy. One part grows leaner, smarter, and more productive. The other becomes excluded, deskilled, and disconnected. The UK’s own stock market sits near record highs. Yet job vacancies for permanent staff have declined at their steepest rate since August 2020, according to the Recruitment and Employment Confederation. The productivity paradox is no longer a curiosity; it is a risk.

As AI reshapes economies, governance is no longer a contest between nations—but between private influence and public authority.

Compounding this is a more concerning development: the growing concentration of economic and technological power. A small cadre of tech companies now control the infrastructure, data, and models that underpin modern AI systems. These companies increasingly shape not just markets but societal outcomes education, employment, and even democratic discourse. The combined market capitalisation of the so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’ tech companies Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, NVIDIA, and Tesla, now accounts for over 35% of the total value of the S&P 500 index, equivalent to more than $13 trillion as of July-2025. This concentration of economic power gives them extraordinary influence not only over global competition but also over regulatory environments and national policy agendas. NVIDIA alone is now valued more than the entire energy sector of the S&P, serving as both the engine room and enabler of AI development across industries. and the economic leverage they hold over both competitors and regulators. In some cases, their market value and contribution to GDP rivals that of nation-states and raises an important question: if AI is reshaping economies who is governing AI?

There are some organisations such as Mistral, Hugging Face, and DeepSeek who are leading open-source initiatives designed to decentralise access to foundational models and reduce systemic dependency on closed ecosystems. While these efforts reflect a broader ambition to democratise AI development, they remain limited in scale and influence compared to the dominance of proprietary platforms. Whether open innovation can meaningfully counterbalance concentrated control remains to be seen, but it signals an important evolution in how power may be distributed in the AI economy.

This question of who is governing AI? demands a serious policy response, one that may ultimately require coordination not just at the national level, but globally. The challenge is not simply technical, but institutional: how do we ensure that governance keeps pace with capability, and that public interest keeps pace with private innovation.

The UK must act decisively through responsive regulation, reimagined education, and a fair redistribution of AI’s economic gains to ensure no one is left behind.

First, we need a regulatory framework that is fit for purpose. That means moving away from legacy approaches and toward one that is responsive to how AI is used in the real world. Regulation should scale with impact; light-touch where risk is low, but rigorous and enforceable where livelihoods are at stake. AI systems that track employee productivity, assign working hours, automate recruitment, or displace human roles must face the same level of scrutiny as financial services or critical infrastructure. Done well, regulation won’t stifle innovation, it will ensure it is trustworthy, ethical, and aligned with long-term public interest.

Second, we must reimagine the skills agenda and align it more deliberately with the UK Government’s Industrial Strategy. While the government has made important commitments to AI upskilling, these interventions alone are not enough. What is required is a national, cross-sector commitment to wholesale education reform. The shift to an AI-powered economy demands more than just short-term training, it calls for a complete overhaul of how we prepare our children and future workforce for a world where AI is a fundamental part of every job. That means equipping them with AI literacy, technical adaptability, and the ability to collaborate effectively with intelligent systems from the earliest stages of education. Unless the education system is urgently updated, a significant portion of society risks being left behind by the pace of technological change.

Third, we need a mechanism to share the economic gains of AI more fairly. A targeted AI Displacement Levy applied to firms that reduce headcount through automation could fund a National Transition Fund. This would support workers through retraining, wage support, and access to roles in mission-critical sectors like care, education, and the green economy. It’s not about penalising progress; it’s about ensuring progress works for everyone.

Business also has a role. AI cannot be treated solely as a cost-saving tool. Corporate leaders must ask whether their deployment strategies strengthen or fragment their workforce. At Digital Futures, these are daily considerations. AI must be made to serve missions, not just margins.

The AI transition is not merely an economic event; it is a national moment of reckoning. It challenges our institutions, our industries, and our collective sense of purpose. The decisions we make now will shape not only our competitiveness, but the very fabric of our society. We must reject the notion that technological progress is something to be managed passively or left solely to the market. Instead, we must actively shape it – through policy, through investment, and through a shared commitment to the common good.

This is a generational responsibility. Government, business, and civil society must come together to ensure that AI does not divide the country between those who build the future and those who are excluded from it. We need a national effort as ambitious as any in our recent history. One that invests in people, aligns with our values, and ensures the United Kingdom remains not only a global leader in innovation, but a beacon of inclusive growth.

The question is no longer whether AI can deliver prosperity. The question is whether we, together, have the courage and coordination to deliver it for everyone.

References:

Digital Futures was founded to challenge outdated workforce models and redefine how organisations build capability in an AI-driven economy. We partner with the world’s most innovative companies and forward-thinking governments to reimagine workforce strategy – ensuring AI is deployed with purpose, unlocks opportunity and delivers lasting societal impact.

Engineering Tomorrow. Together.